Intermediate problem-solving techniques

Every problem we face is different.

But some are more complex than others.

Solving these problems requires an extensive toolkit of techniques, from triangulation to removing biases. These intermediate problem-solving techniques can help leaders cut out groupthink, use their team's wisdom, and spot biases in their decision-making process.

This guide will teach you how to master intermediate problem-solving techniques and overcome biases in the process.

Table of contents:

The magic of triangulation

As the old saying goes, “It ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble—it's what you know for sure that just ain't so.”

Making decisions without data or reasoning is a dangerous move for businesses. Thankfully, a technique called triangulation can help leaders avoid this. Triangulation is when multiple sources of information are used to arrive at an answer—increasing the likelihood of the answer being correct.

There are four main methods of Triangulation:

1. Analytical + Intuitive

This triangulation approach relies on combining intuition and analytics.

A great example of this? Star Trek.

The ship's leader, Captain Kirk, based his decisions on intuition. However, his second in command, Mr. Spock, was grounded in logic analysis.

This combination of decision-making styles allowed the two to combine forces and make the best decisions for their team.

2. Wisdom of crowds

The next approach is using the wisdom of the crowds.

Picture this: A jar of M&Ms is placed in front of you, and you must guess the exact number in the jar.

James Surowiecki, a staff writer at the New Yorker who wrote a book on the wisdom of crowds, noticed a pattern when people try to guess the number of marbles in a jar. It's unlikely an individual will make an accurate guess. But, time and time again, the average guess of the number in the jar turns out to be amazingly accurate.

Why?

It's because the group feeds off each other's guesses and groups their knowledge until they find the right answer—proving there is wisdom in crowds.

3. Top-down and bottoms-up

Top-down thinking starts with the answer and builds out the details to confirm it, whereas bottoms-up thinking uses details to arrive at an answer.

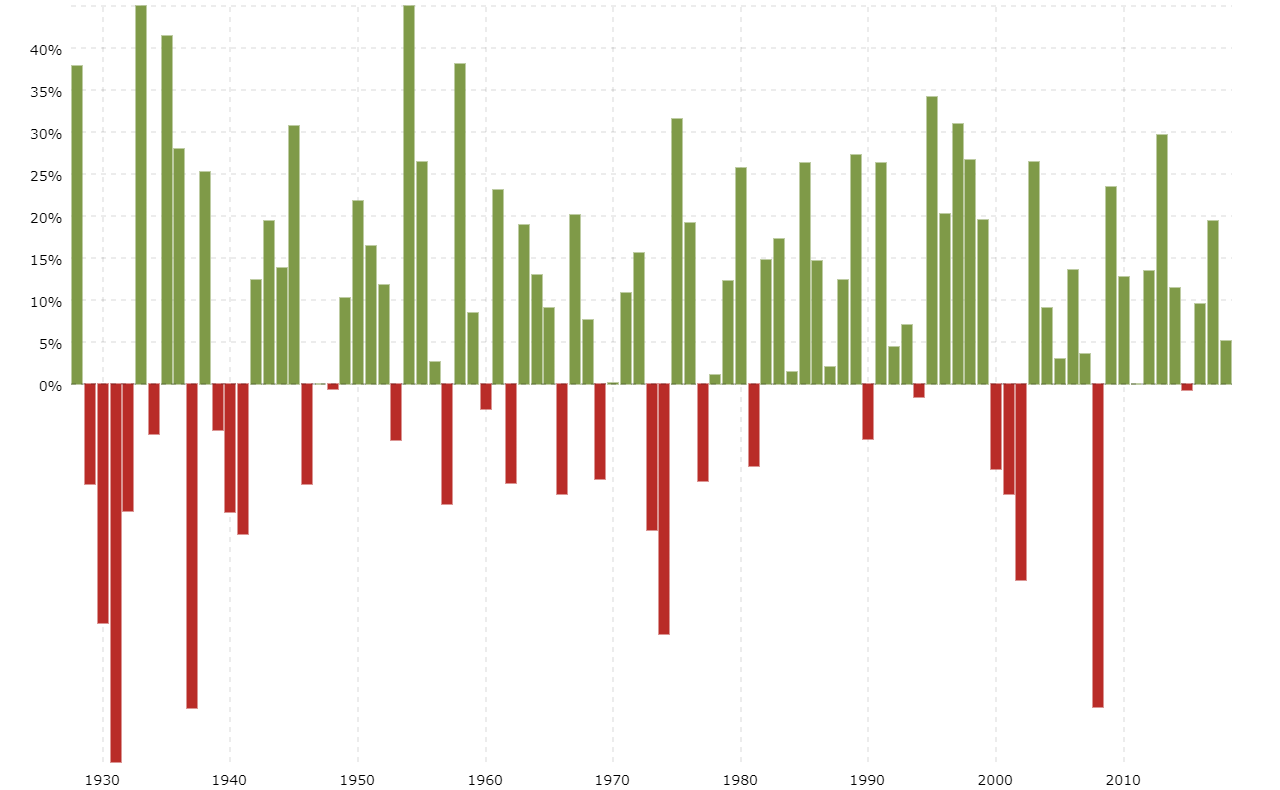

Take the S&P 500, for example.

If you are trying to estimate annual returns for the index fund, its historical gains of 6-8% can be used to create a one-year forecast. This is an example of a top-down approach.

A bottoms-up approach would look at the 500 companies in the fund and estimate each share price in a year. That information would then be used to accurately forecast the entire index fund.

4. Multiple data sources

The final approach to triangulation is using multiple data sources.

Data is perfect for removing bias from decision-making. Some leaders like an internal team analysis or input from their leadership team. Others prefer expert interviews or external benchmarking to gather this data. Either way, using sources other than your own assumptions can help remove bias and arrive at a decision based on data.

An introduction to biases

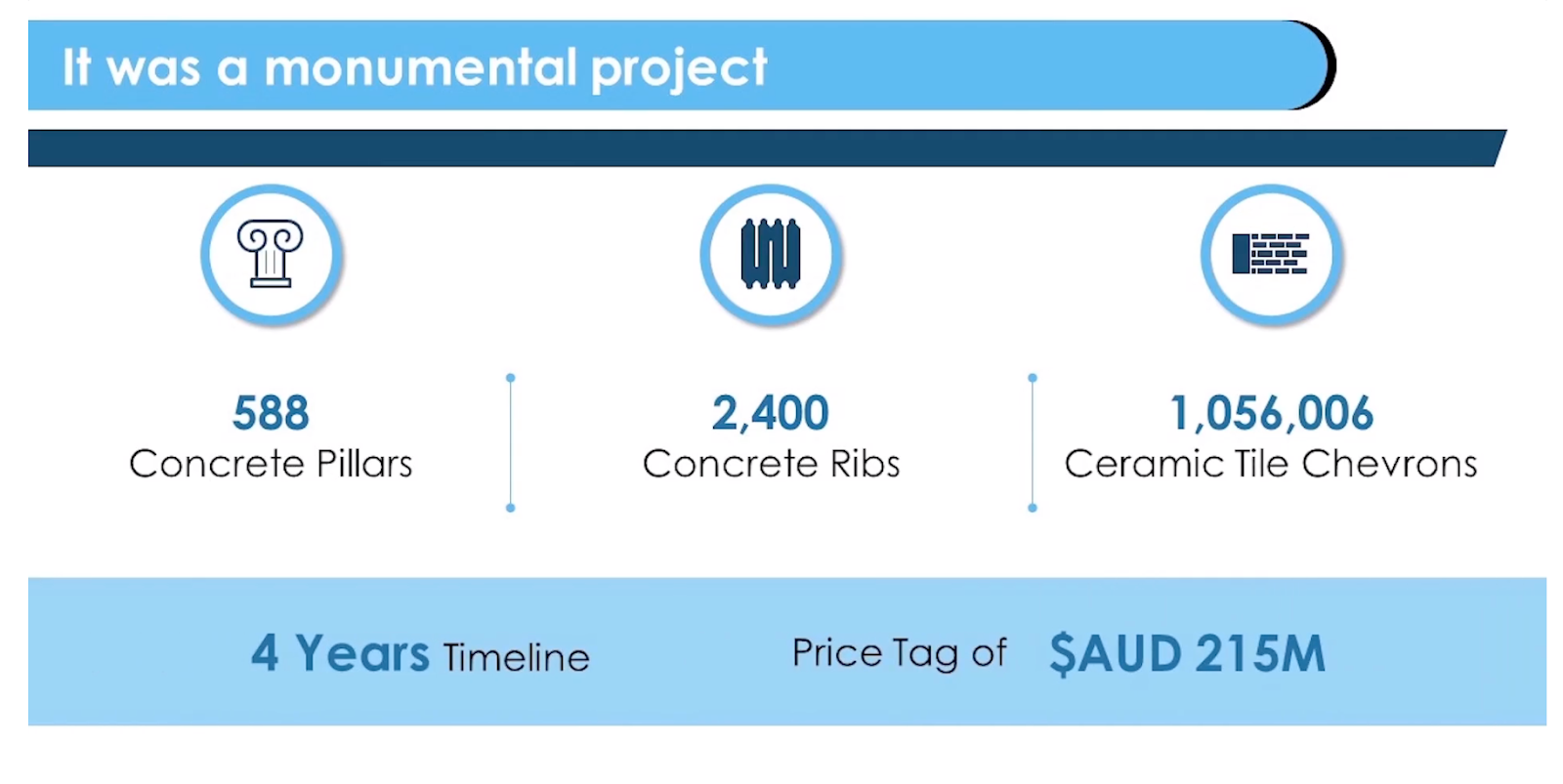

When the iconic Sydney Opera House had its groundbreaking ceremony in 1959, it was a monumental feat.

The project had tons of moving parts, with hundreds of concrete pillars, ribs, and ceramic tile chevrons to piece together. New South Wales Premier Joseph Cahill set the project's budget at $215 million and gave it a timeline of just four years.

Unfortunately, the project fell victim to biases during the build, becoming one of the most disastrous project failures of all time. Instead of taking four years, it took fourteen. The $215 million budget also exploded into $3.1 billion—a 1,340% jump.

So, how could the project go so far off the rails?

The build fell prey to a cognitive bias called planning balancing. This is when systematic errors and thinking affect our decisions in the planning fallacy, and we believe everything will fall into place and follow a "best case" scenario.

Although this is just one bias among 18 to be aware of, knowing when they're creeping into your decision-making makes it easier to overcome them.

How to overcome biases when solving problems

Biases are all around us, and there's a reason our brains gravitate towards them.

Humans love to take shortcuts when processing information and skip to conclusions. Or if there's too much data to process, we will fall back on what we think is true. We are also biased by our emotions, motivations, and memories.

Last but not least, the people around us can influence our thinking. When we listen to the opinions of others, it can stop us from thinking differently.

Biases can significantly impact our ability to make unbiased decisions. But if you know how to spot your biases, it's easier to challenge them. Here are 18 main biases you should be aware of:

- The anchoring effect

When we rely too much on an initial piece of information when making decisions.

Example: "But the first part of the quote I saw was okay, do we need to look anymore?"

- The availability heuristic

Overestimating the importance and likelihood of events when more information is available.

Example: "I saw something very similar to this on LinkedIn, so we need to take it seriously."

- The bandwagon effect

The uptake of beliefs and ideas increases when they've been adopted by others.

Example: "The whole department knows there's no problem here."

- The belief bias

When we base the strength of an argument on believability and that the plausibility of the conclusion is correct.

Example: "I didn't quite follow your argument, but the conclusion seems about right."

- The blind spot bias

A belief that we have less bias when making decisions than others.

Example: "Let's ignore Sarah's views on this one. She's biased!"

- The clustering illusion

Overestimating the importance of small clusters and patterns in larger data sets.

Example: "This is the second week in a row that this has happened. There must be a problem."

- Confirmation bias

Focusing on information that only confirms existing preconceptions.

Example: "We did loads of simulations, and most of them showed there's no problem." - Courtesy bias

Reaching a conclusion that's more socially acceptable to avoid offense or controversy.

Example: "The last time we discussed this, the meeting lasted for hours. Let's move on."

- The endowment effect

Adding more value to things because we already own or have them.

Example: "I know it will cost you a fortune to fix, but it cost us $15,000. We can't just throw it away."

- The gambler's fallacy

Believing future probabilities are altered by past events, even though they're unchanged.

Example: "The conveyor belt broke three times last month. It's pretty unlikely it will happen again."

- Hyperbolic discounting

Aiming for a smaller, quicker payoff over a larger reward down the road.

Example: "Let's just get the deal done ASAP!" - The illusion of validity

Overestimating our ability to make predictions, especially when the data tells an accurate story.

Example: "This worked fine in the factory in Korea. It should work fine here."

- The ostrich effect

Avoiding negative financial information by pretending it doesn't exist.

Example: "Looks like we ran out of time to discuss this."

- Post-purchase rationalization

Retroactively labeling decisions as positive to rationalize them.

Example: "We made a good call on that one."

- Reactive devaluation

Devaluing an idea because it came from an opponent.

Example: "Our competitors are only doing well because their products are cheap."

- Risk compensation

Taking bigger risks when it feels safer, but being more cautious when risk increases.

Example: "Now we've got the new equipment, we can cut the time spent on maintenance."

- Status quo bias

Sticking with what you have over change.

Example: "If it isn't broken, don't fix it."

- Stereotyping

Assuming a person has characteristics because they're a member of a group.

Example: "Dave from tech is worried that the tech team is always seen as pessimistic."

⚡ Prezent Pro Tip: To reduce or remove your biases, try these techniques:

- Play the challenging role. Agree to consciously avoid being part of the group think in your team. Challenge existing assumptions.

- Set early criteria. Create the right guardrails for the problem being solved.

- Build sensitivity models. Assess the impact of changes in key variables on your project.

- Be self-aware. Check yourself for any biases at every stage of the decision-making process.

Expert Corner: How Ajay Gupta simplifies and solves problems

Ajay Gupta has spent 30 years as a Senior Partner at McKinsey and Company.

Over the years, he has faced many problems and learned that asking the right question during the problem-solving process is half the battle.

Here are some of his best tips for simplifying problems so they're easier to solve.

Look for the root cause of a problem

Gupta always encourages clients to be curious and always ask themselves: what are the root causes for something, and what are the causal relationships between the different pieces?

Start with understanding the context of a question. Complex problems usually have multiple phases, so structuring them helps break them down into components and analyze them in detail.

Gupta says understanding causality and what happens when each piece gets impacted will help you see the bigger picture when figuring out the root cause of a problem.

Find and analyze the data

Some types of problems have lots of data, and seeing patterns in the numbers is crucial.

Gupta says it's important to get to the insights and know what the numbers are telling you, which all come during the synthesis phase of solving a problem. Pull back and ask yourself, what is this structuring and analysis telling us? What are the big-picture messages? Have we tested different underlying assumptions?

Boiling down the data takes time, but the insights are more useful.

Wrapping up

Every business is at risk of being paralyzed by poor decision-making and the inability to overcome internal biases.

The good news is these common problems can be caught early—and avoided—with the right techniques. Break down the problem, look for data, and challenge your existing assumptions. Then, use analytical approaches and lean on the wisdom of your team to get closer to an accurate answer.

Successful problem-solving takes time—but use these techniques to ensure the answer will always be the right one.